Context

APIs are everywhere, and it’s critical to have ways to efficiently test that they work correctly. There are several tools out there that are used for API testing, and the vast majority will require you to write the tests from scratch, even though in essence you test similar scenarios and apply the same testing techniques as you did in other apps/contexts. This article will show you a better way to tackle API testing that requires less effort on the “similar scenarios” part and allows you to focus on the more complex part of the activities.

Testing APIs

When thinking about testing APIs, from a functional perspective, there are several dimensions which come to mind:

-

verifying the structure of the exchanged data i.e. structural validations (length, data type, patterns, etc). This is where you send a 2 character string when the API says the minimum is 3, you put a slightly invalid email address, an slightly invalid format for a date field and so on.

-

boundary testing and negative scenarios, similar a bit to the above, but focusing on “breaking” the application. This is where you go to the extreme: you send extremely large values in Strings, extremely positive or negative values in Integers and so on.

-

behaviour according to documentation i.e. APIs are responding as expected in terms of HTTP status codes or response payloads. This is where you check that the service responds as documented: with a proper HTTP response code (2XX for a success, 400 for a bad request, etc) and a proper response body.

-

functional scenarios i.e. APIS are working as expected in terms of expected business behaviour. This is where you check that the response body contains the right business information: when you perform an action (like creating an entity, altering its state) the service correctly responds that the action was performed and with relevant information.

-

linked functional scenarios i.e. you create an entity and you get its details after to check they are the same. This is where you get a bit more end-to-end and you perform an action (like creating an entity) and with the return identifier you go and check the existence (you do a GET based on the identifier)

Ideally all the above scenarios must be automated. And it’s achievable to do this for the last 2 categories, but when having complex APIs with lots and lots of fields within the request payload, it becomes very hard to make sure you create negative and boundary testing scenarios for all fields.

What are the options for API test automation

There are several frameworks and tools on the market which can help to automate all these. Just to name a few:

They are all great tools and frameworks. You start writing test cases for the above categories. The tools/frameworks will provide different sets of facilities which might reduce specific effort during implementation, but ultimately you end up writing the actual tests to be executed (i.e. code). Even if you’ve done this before, and you know exactly what to test, even if you create a mini-framework that provides facilities for the common elements, you still need to write a considerable amount of code in order to automate all your testing scenarios.

And what happens when the API changes a bit? Some fields might be more restrictive in terms of validation, some might change the type, some might get renamed and so on. And then the API changes a bit more? This is usually not very rewarding work. Software engineers are usually creative creatures, and they like challenges and solving problems, not doing boring stuff. There are cases when one might choose to leave the API as is in order to prevent changing too many test cases.

Is there a better way?

But what if there is an alternative to this, and the first 3 categories above can be fully automated, including the actual writing of the test cases. And also make the next 2 categories extremely simple to write and maintain.

This is why CATs was born!

CATs has 3 main goals in mind:

- remove the boring activities when testing APIs by automating the entire testing lifecycle: write, execute and report of test cases

- auto-heal when APIs change

- make writing functional scenarios as simple as possible by entirely removing the need to write code, while still leveraging the first 2 points

CATs has built-in Fuzzers which are pre-defined test cases with expected results that will validate if the API response as expected for a bunch of scenarios:

- send string values in numeric fields

- send outside the boundary values where constraints exist

- send values not matching pre-defined regex patterns

- remove fields from reuqests

- add new fields inside the requests

- and so on…

You can find a list of all the available Fuzzers here: https://endava.github.io/cats/docs/fuzzers/.

There is one catch though. Your API must provide an OpenAPI contract/spec. But this shouldn’t be an issue in my opinion. It’s good practice to have your API documented in a tools-friendly format. Many companies are building OpenAPI specs for their API for easier tools integration.

Using CATs

Let’s take an example to show exactly how CATs works. I’ve chosen the Pet-Store application from the OpenAPITools example section.

The OpenAPI spec is available in the same repo: https://github.com/OpenAPITools/openapi-petstore/blob/master/src/main/resources/openapi.yaml.

Looking at the contract, how much time would you estimate would take to create an automation suite to properly test this API? 1 Day? 2 Days? Several days?

Using CATs, this will probably be a couple of hours.

Let’s start the pet-store application on the local box first (you need to have Docker installed):

docker pull openapitools/openapi-petstore

docker run -d -e OPENAPI_BASE_PATH=/v3 -p 80:8080 openapitools/openapi-petstoreThis will make the app available at http://localhost for the Swagger UI, and the API will be available at http://localhost/v3.

Download the latest CATs version. Download also the openapi.yml from above.

Before running CATs, please read how it works in order to better interpret the results.

Running the built-in test cases

You can now run:

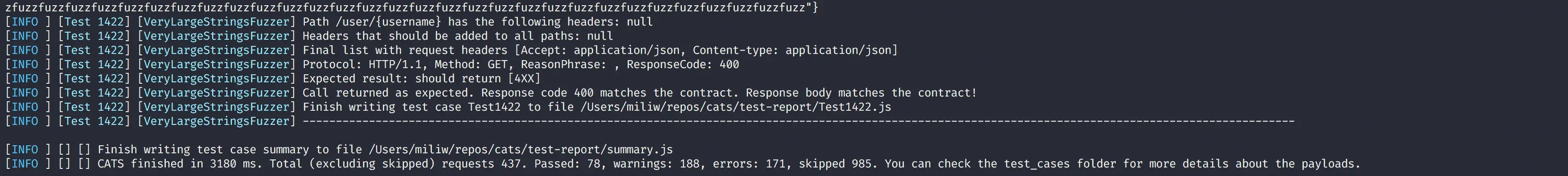

cats --server=http://localhost/v3 --contract=openapi.ymlYou will get something like this:

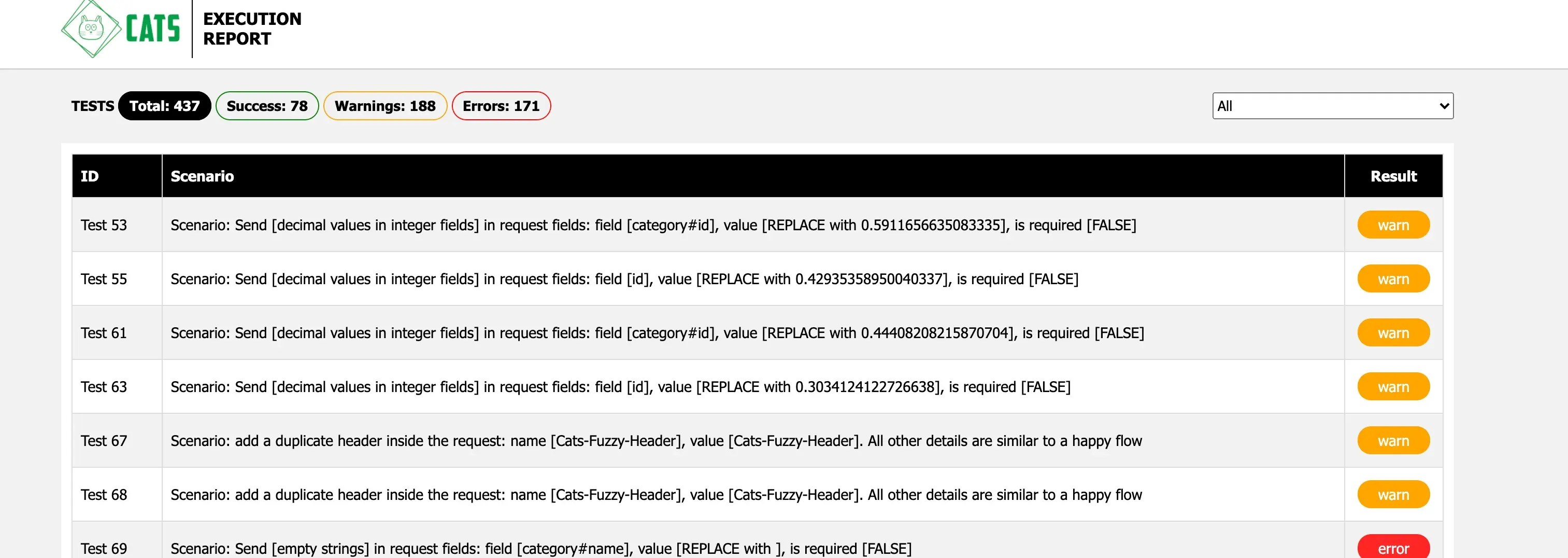

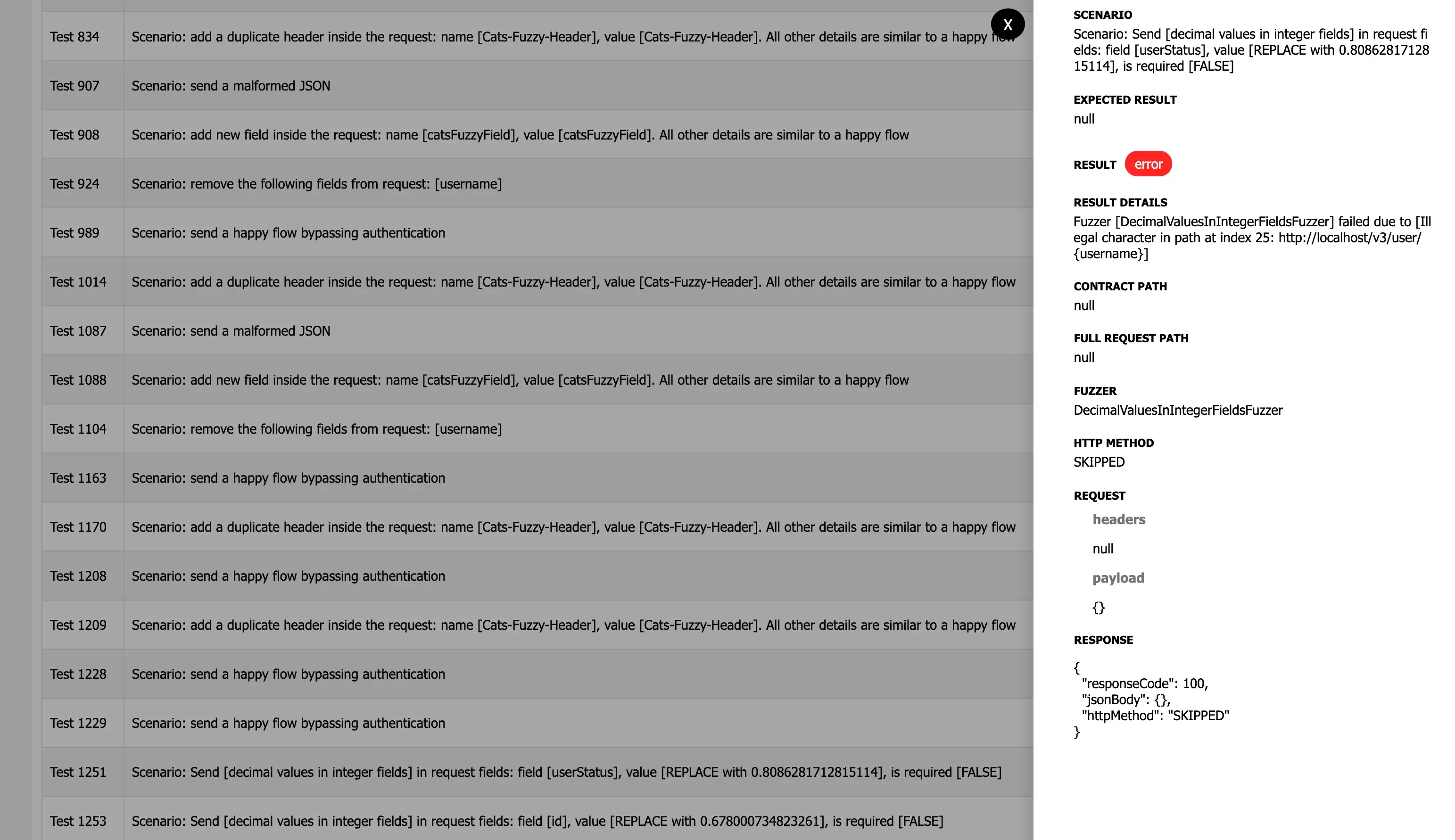

Not bad! We just generated 437 test cases, out of which 78 were already successful, and we’ve potentially found 181 bugs. To view the entire report, just open test-report/index.html. You will see something like this:

Now let’s check if the reported errors are actually bugs or just configuration issues. We will deal with the warnings after.

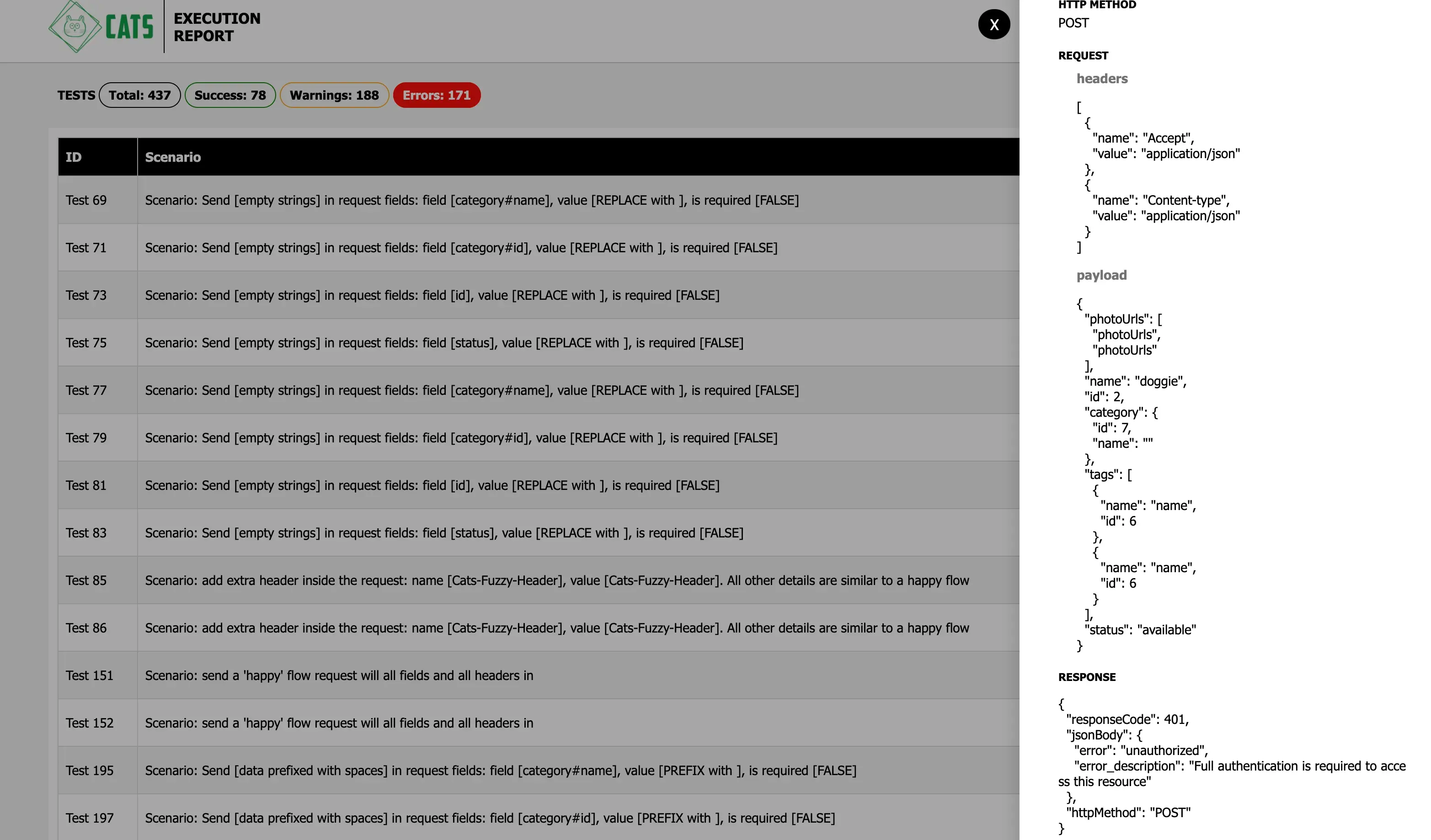

Checking the first failing test (just click on the table row) we can see that the reason for failing is actually due to the fact that we didn’t send any form of authentication along with the requests.

Looking in the openapi.yml we can see that some endpoints require authentication while some others require an api_key.

CATs supports passing any type of headers with the requests.

Let’s create the following headers.yml file:

all:

Authorization: Bearer 5cc40680-4b7d-4b81-87db-fd9e750b060b

api_key: special-keyYou can obtain the Bearer token by authenticating in the Swagger UI. The api_key has a fixed value as stated in the pet-store documentation.

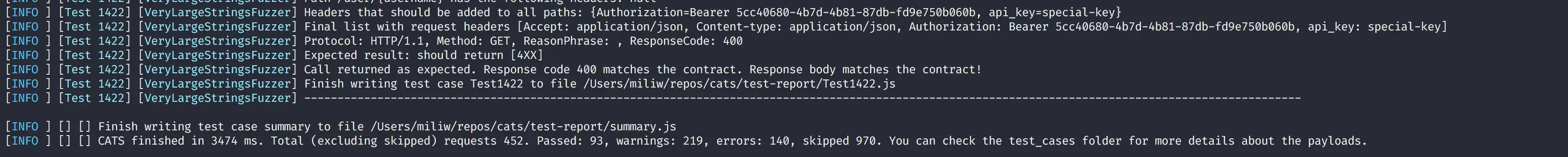

Let’s do another run, including now the headers.yml file:

cats --contract=openapu.yml --server=http://localhost/v3 --headers=headers.ymlA bit better now. 93 successful and 140 potential bugs.

Again, let’s check if there are any configuration issues, or they are valid errors. Looking at test 1253 we can see that the target endpoint has a parameter inside the url.

This is a limitation of CATs as it cannot both fuzz the URL and the payloads for POST, PUT and PATCH requests. And looking at the contract, indeed, there are several other endpoints that are in the same situation.

For this particular cases CATs uses the urlParams argument in order to pass some fixed values for these parameters. The provided values must result in existing HTTP resources so that the fuzzing works as expected.

We run CATs again, considering also the urlParams:

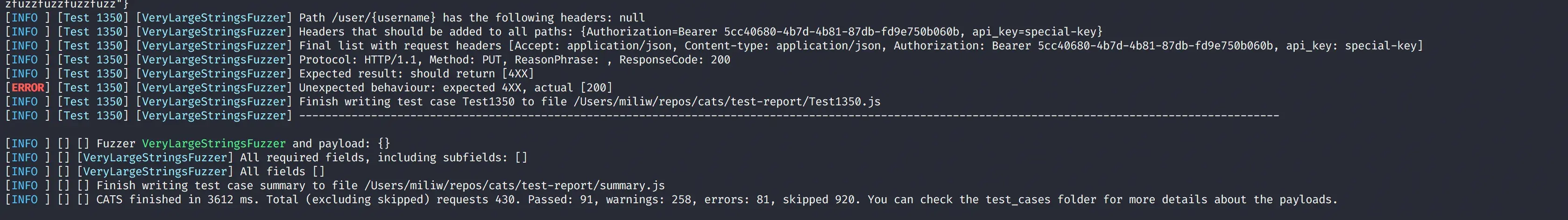

cats --contract=openapi.yml --server=http://localhost/v3 --headers=headers.yml --urlParams="username:username,petId:10,orderId=1"91 passed test cases and “just” 81 potential bugs.

Let’s check again if these are actual errors. This time, they all seem to be valid bugs:

Test 429: the server returns a500 Internal Errorinstead of a normal200empty responseTest 520:CATsinjects a new field inside the request, but the server still responds with200instead of returning a400 Bad RequestTest 523:CATssends a null value in a non-required field (according to the contract) and expects a2xxresponse, while the server replies with500 evend ID cannot be null- and so on…

We now truly have 81 bugs which must be fixed in order to have a stable service.

Now, going into the warnings zone, these are usually tests which fail “just a bit”. The server usually responds withing the expected HTTP response code family, but either the HTTP status code is not documented inside the contract, or the response body doesn’t match the one documented in the contract.

Either way, these also must be fixed as it shows that the OpenAPI spec is incomplete or that the actual implementation deviated from it.

Looking at what we’ve got at the end, with a small effort investment we were able to “write”, run and report 430 test cases which otherwise would have taken significant more effort to implement and run. We have both validation that the service works well in certain areas, it must update the OpenAPI specs or tweak the service to response as expected and got a list of bugs for behaviour which is not working properly.

Running custom test cases

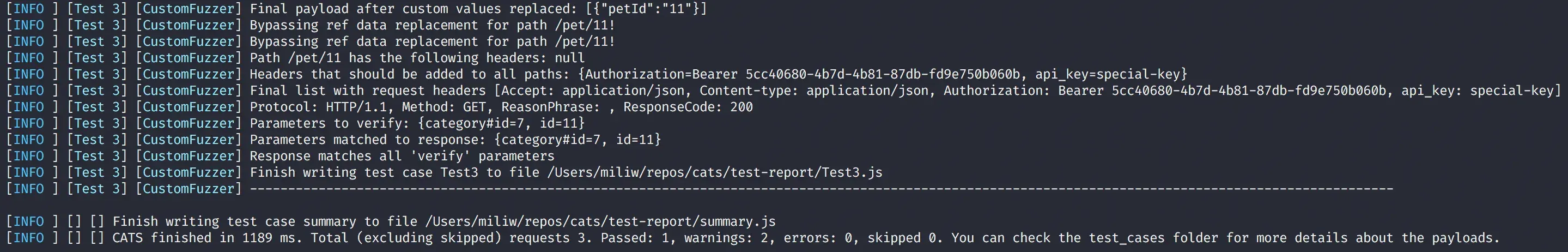

But we can do even more. As mentioned previously CATs also supports running custom tests with minimal effort. This is done using the FunctionalFuzzer.

The FunctionalFuzzer will run tests configured within a FuntionalFuzzer file that has a straightforward syntax.

The cool thing about the custom tests is that you don’t need to fill in all the details within the request, just the fields that you care about.

Below is an example of running 2 simple test cases that create a Pet and verify the details of a Pet. This is saved as functionalFuzzer-pet.yml. (Ideally we should correlate these 2, but it seems that the pet-store API is not returning an ID when you create a Pet).

/pet:

test1:

description: Create a new Pet

name: "CATs"

expectedResponseCode: 200

/pet/{petId}:

test2:

description: Get the details of a given Pet

petId: 11

expectedResponseCode: 200

verify:

id: 11

category#id: 7We now run CATs again (notice the cats run sub-command):

cats run --contract=openapi.yml --server=http://localhost/v3 --headers=header_pet.yml functionalFuzzer-pet.ymlAnd we get the following result:

The 2 warnings are also due to the fact that the response codes are not properly documented in the OpenApi contract.

And you get the same benefits as when writing the test cases using actual code:

- you can choose the elements to verify in the responses, using the

verifysection - you can check for expected HTTP status codes using

expectedResponseCode - and you can even pass values from one test to another using

output

As mentioned above, ideally, when getting the Pet details, you should pass an ID received when initially creating the Pet to make sure that is the same Pet. The functionalFuzzer-pet.yml will look like this:

/pet:

test1:

description: Create a new Pet

name: "CATs"

expectedResponseCode: 200

output:

pet_d: id

/pet/{petId}:

test2:

description: Get the details of a given Pet

petId: ${pet_id}

expectedResponseCode: 200

verify:

name: "CATs"What about auto-healing

Auto-healing is built in. As CATs generates all its tests from the OpenAPI contract, when the API updates i.e the OpenAPI contract updates also, CATs will generate the tests accordingly.

Conclusions

CATs is not intended to replace your existing tooling (although it might do it to a considerable extent).

It’s a simple way to remove some of the boring parts of API testing by proving built-in test cases which can be run out-of-the box.

It also makes sure it covers all fields from request bodies and has a good tolerance for API changes.

In the same time, it might be appealing for people that want to automate API test cases, but might not have the necessary skills to use tools required significant coding.

Why not give it a try?